So, what don't you know?

There are a number of interesting aspects to the region that we have been discovering. If it was Australia there would be tourist signs aplenty, and entrepreneurs making the most of the attraction ... but this is Kenya. Outside the game parks there are few tourists, and not enough disposable income to support tourist ventures.

1. Barack Obama was born in Hawaii. His mother was born in the mid-West of the USA, but his father was born in Kenya. It was in a little town called Nyangoma Kogelo, which is about 80 km south-West of our village. He went on to study in the US, and after returning to Kenya (after divorcing Barack's mother) worked his way up into a position as a senior government economist. He died in 1982.

We have not visited the town as it is not really on the way to anywhere. It seems as though most Kenyans are very proud to have the father of the US president as one of their own.

|

| Iten market |

Past champions have established running camps in Iten. So too have foreign coaches who come to discover the secret of Kenya's success. The small primary school of St Patricks has produced an astounding number of world champions, both male and female.

The town itself looks like most other Kenyan communities; run-down shops that needed a paint twenty years ago, sellers in open markets, piles of rubbish along the roadsides. However, if you are there early in the morning or late in the evening, you will see hundreds of runners pounding the streets, some of them current world champions.

Also, just North of the town is an impressive lookout with views across a wide, fertile valley.

What is their running secret? There seems to be no single answer. It is a combination of barefoot running to school as children, a front-foot running style where runners land on their toes not their heels, the altitude, and the desire to use running as a way out of poverty.

|

| View from Iten Lookout |

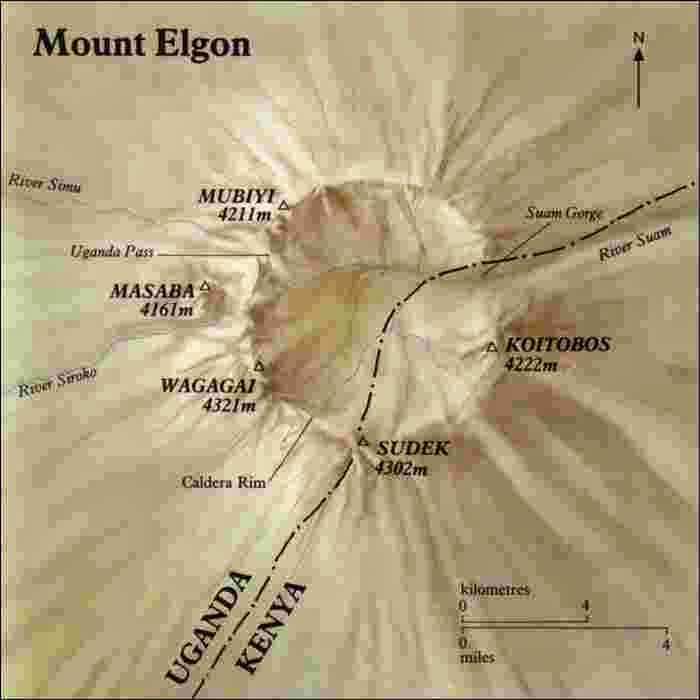

We hope to travel to this mountain soon. You can drive to a car park and then walk for two hours to one of the high peaks. The highest peaks are across the border in Ugandan, so we won't be going to the summit, but it would be nice to reach the rim.

This mountain is also famous because it contains caves with salt that accumulates on the walls. Elephants enter the caves and are known to lick the salt from the walls. We have not seen an elephant in Kenya so it would be wonderful to see them in or around the caves.